Seven statistics and three main keys point the way toward staying on the course

January 12, 2017 by Josh Woods in Analysis, Instruction with 0 comments

Injuries can be rich learning experiences. When I was ten, for instance, I learned that leaping off a garage roof with a beach umbrella is pretty much the same thing as leaping off a garage roof without a beach umbrella.

Having sustained several flamboyantly unnecessary injuries, I probably shouldn’t be giving advice on how to avoid them. Still, my goal here is not to air my own wisdom, but rather to add to yours by cultivating some available resources.

Since disc golf established a competitive footing in the early 1970s, researchers have published a remarkably small number of academic papers on the sport. Consider, for instance, the studies of disc golf available through JSTOR, one of the largest digital libraries of academic journals in the world.

A JSTOR search for “disc golf” currently returns zero studies devoted to the sport, while hundreds of articles have investigated mainstream athletics such as football and baseball. Even darts (332 articles) and knitting (43 articles) receive far more attention from scholars than flying discs.

Still, a few disc golf studies do exist. In the last year or so, two papers have examined disc golf injuries. My aim here is to review these studies and offer tips for avoiding injury based on an interview with health-and-fitness expert Seth Munsey.

To begin, here are the seven most interesting disc-golf injury statistics:

1) Eight out of ten disc golfers have sustained an injury.

With help from the PDGA, Dr. Joseph Nelson and his colleagues recently surveyed 874 disc golfers, and found that 715 of them experienced at least one injury from playing disc golf1. This percentage is higher than the injury rate of several other sports2. Although a second study conducted by Rahbek and Nielsen produced a lower estimate, the authors of both studies seemed surprised by the significant health risks involved with this low-intensity, non-contact sport3.

I’ve had three separate injuries myself, but even I was a little surprised to learn that more than 80 percent golfers, at some point, leave the course in pain, and some head for the hospital.

2) Pros are more likely to sustain injuries than amateur disc golfers (including older amateurs with high BMIs who don’t warm up).

The study by Rahbek and Nielsen examined eight risk factors for injury, including age, body mass index (BMI), years of experience, average score, warm-up, number of discs carried, tournaments played, and PDGA division. Only three of these factors are associated with injury. Professionals who play several tournaments and card lower scores are more likely to sustain injuries than amatuers who play fewer tournaments and score higher. This makes sense on its face. People who throw more discs accumulate more risk of injury, even in players with exceptional technique.

More interesting were the non-findings. As an overweight, aging disc golfer, I was happy to learn that age and BMI were not significantly related to injury. As I discussed in a previous article, I was also surprised to find that disc golfers who warm up prior to playing were more likely to sustain injuries than those who do not warm up. I should note, however, that warming up, along with years of experience and number of discs carried, were not statistically significant predictors of injury.

3) Forehand throwers are more prone to injury than backhanders.

Per the Nelson study, most disc golfers — 86 percent — are predominately backhand throwers. Only 13 percent reported the forehand as their most common throwing style, and one percent said they used mostly overhead throws. Disc golfers who throw backhand were not at a greater risk of any type of injury compared to those who throw forehand. But forehand throwers were more likely to have an elbow injury than backhand throwers. Overhead throwers were excluded from the analysis due to the small sample size, but both studies suggested that this may be the most hazardous type of throw.

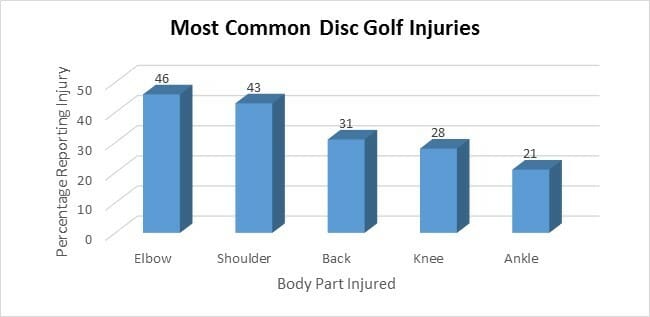

4) The elbow is the most commonly injured body part.

Among the 715 injured disc golfers in the Nelson study, 46 percent experienced injuries to the elbow, followed by the shoulder at 43 percent. The study by Rahbek and Nielson also found that the elbow and shoulder were the first and second most common problem areas. The shoulder injury rate in disc golf is close to that of other upper-arm sports such as volleyball, basketball, and tennis4.

5) Disc golf injuries to the back and knee are common, and often lead to long-term problems.

Although they afflict fewer disc golfers, injuries to the back and knee can be especially costly in terms of pain and downtime, and they often reoccur. Disc golf luminaries Paul McBeth and Simon Lizotte have suffered from back and knee injuries, respectively. Lizotte underwent knee surgery in October, missing part of the 2016 season, and he remains unsure about when his 2017 season will begin.

6) Many disc golf injuries require serious medical attention

Disc golf injuries are usually minor and go untreated. When asked about their “most serious injury,” 32 percent of the respondents in the Nelson study said that they did not receive any treatment. Still, roughly 7 out of 10 injuries required some type of medical attention or therapy, and 115 of the 715 injured respondents underwent surgery. The study by Rahbek and Nielson produced lower estimates of the number of disc golf injuries requiring medical treatment and surgery.

7) Overuse is the primary cause of disc-golf injuries.

Roughly 60 percent of respondents in the Nelson study said that their injury “occurred gradually over time due to repetitive stresses;” about a third experienced a traumatic injury during a single throw (ouch), while smaller shares reported a fall or some other injury mechanism. Rahbek and Nielson produced similar results. In short, repetitive stress injuries pose the greatest risk to disc golfers.

Staying off the sideline

During my last checkup, I complained to my doctor, “I eat too much, drink too much, work too much, and play too much.”

To my amazement and delight, he said, “me too.” Then, after a shared chuckle, he said, “but the trick is to do too much in a way that doesn’t kill you.”

Elegant advice, I thought, and certainly applicable to disc golf. Whether you’re a professional trying to get an edge on the competition, or an amateur who’s got “the bug,” many of us feel the urge to play too much disc golf. The most important piece of advice offered by the studies reviewed above is as obvious as it is hard to follow: Don’t overuse your throwing arm. If you play one too many rounds in a day, you’ll have the devil to pay.

In more technical terms, per Rahbek and Nielson:

“Gradual onset injuries … are presumably caused by cumulative micro-damage to the tissues, following a period of excessive loading of the tissues or insufficient recovery. As intermediate and professional players perform more throws and participate in a greater number of hours per week of disc golf than amateurs, such accumulation could potentially occur during the many repetitive forceful throws and ultimately lead to injury, even in players with highly developed kinetic chain functional strategies.”

Knowing when to say when is the key to disc golf health, but there may be things we can do to prepare our bodies for heavy use.

To learn more about such preparations, I contacted Seth Munsey of Disc Golf Strong. Munsey holds a degree in kinesiology from Cal State Fullerton, owns a gym in Sand City, California, worked as a strength coach for the Anaheim Ducks, a professional hockey team, and may be the only professional trainer on the planet who is focused on the health and fitness of disc golfers.

Munsey wasn’t surprised by disc golf’s 80 percent injury rate. He suggested that most people underestimate the athleticism involved with throwing a disc. “If you play disc golf,” he said, “you are an athlete.”

Munsey’s insistence on moving disc golf beyond the beach-Frisbee stereotype and appreciating the formidable physical demands of the sport signal, if faintly, disc golf’s emergence as a serious, institutional endeavor.

Most big-time collegiate and professional sports organizations have embraced sports science for both performance training and injury prevention. Munsey’s general aim is to push disc golf in this direction.

I took away at least three interesting ideas from our 45-minute interview. First, Munsey confirmed the studies discussed above, suggesting that overuse is indeed the most common cause of injury. Monitoring past injuries, limiting play appropriately and dynamic stretching are keys to training like a professional athlete, according to Munsey.

Second, he noted that avoiding injury also requires proper technique, especially given the substantial biomechanical forces generated by a long-distance drive. Everyone, at some point, has thrown a disc and said, “Wow, that hurt.” Ouch moments usually occur when two undesirable outcomes — overthrowing and poor form — converge.

To improve your technique, consider viewing disc golf throwing clinics on YouTube. For the basics, watch a video by Scott Papa, the Instructional Editor at DiscGolfer Magazine. For a more advanced guide that draws on the biomechanics of throwing, check out Justin Menickelli and Ryan Pickens’ The Definitive Guide to Disc Golf.

And third, to stay off the sideline, Munsey recommends physical training to increase upper-back mobility, hip mobility, and core stability. He offers several videos to help you achieve these goals. I would begin with his introductory clips on upper-back mobility and hip mobility.

He also has a five-part series on “Core Exercise for Disc Golf,” which can be viewed on his Facebook page, where he writes about each exercise in the series and posts the videos.

I’m a skeptic of everyone’s advice — including my own — but I find Munsey’s intellectual curiosity comforting, and the style and substance of his recommendations convincing.

Nelson, J.T., R.E. Jones, M. Runstrom, and J. Hardy (2015). Disc Golf, a Growing Sport: Description and Epidemiology of Injuries. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 3(6): 1-5. ↩

Tenforde, A.S., L.C. Sayres, M.L. McCurdy, H. Collado, K.L. Sainani, and M. Fredericson (2011). Overuse injuries in high school runners: lifetime prevalence and prevention strategies. The Journal of Injury, Function, and Rehabilitation, 3 (2): 125-31. ↩

Rahbek, M.A., and R.O. Nielsen (2016). Injuries in disc golf – A descriptive cross-sectional study, International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 11 (1): 132-40. ↩

Lo, Y.P.C. et al. (1990). Epidemiology of shoulder impingement in upper arm sports events. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 24 (3): 173-177. ↩