The ins and outs of dealing with the physical and mental stresses of competitive disc golf

February 21, 2017 by Alex Colucci in Instruction with 0 comments

Breathing is something we all do all the time, and it’s especially important when participating in an athletic activity. While resting, the average healthy adult takes anywhere from 11 to 18 breaths per minute, which means we inhale and exhale more than 25,000 times each day.

When doing some kind of physical activity, like playing disc golf, the rate of breathing will increase significantly. But how can something so simple be used to your advantage on the course? Let’s take a look at how this basic physical motion can make a significant impact on your mental game.

Breathing and Muscular Function

Disc golf certainly resides towards the less strenuous end of the scale in terms of sporting intensity, at least when considering casual play for recreational purposes. But, during tournament disc golf — when something is on the line and actual success or failure has some material consequences — the intensity is ratcheted up slightly, and the sport becomes both more physically and mentally demanding.

Tournament disc golf (assuming a relatively full field with players on nearly every hole on the course) requires a time commitment of two to three hours at least, per round. All the while you’ll be carrying everything you need on your back (unless you paid up for a cart) essentially hiking between your throws, while anxiously awaiting your turn to get one step closer to the green. Variations in the terrain and weather can also add to the strenuousness. All said, tournament disc golf is an endurance activity.

So a prescient question at this point becomes this: How can we use breathing to make the most of the potential energy in our muscles throughout the hours-long slog of a tournament day?

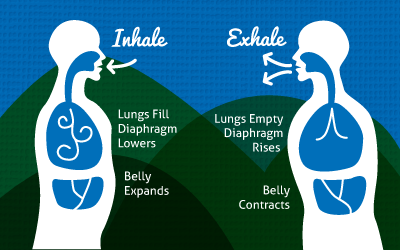

How we breathe — physiologically speaking — can affect how much oxygen makes its way to our muscles. Our thoracic diaphragm, a muscle between our abdomen and lungs, is responsible for both inflating our lungs when we inhale and emptying our lungs when we exhale. Simply put, the more you can empty your lungs when you exhale, the more you can fill them when you inhale. The more you inhale, the greater potential there is for oxygen to be distributed to your muscles where it can help create energy.

But how do we get our diaphragm to more completely empty our lungs when exhaling and more fully fill them upon inhaling?

The diaphragm needs room to move downwards, away from the lungs when you inhale, and needs to be pushed up further towards your lungs when you exhale. Aspects of the technique often referred to as abdominal or diaphragmatic breathing can be utilized to achieve this. Principally, this process involves breathing through one’s abdomen or stomach, rather than through one’s chest. You can practice this by consciously pushing your abdominal muscles and stomach towards your spine when you exhale and then when inhaling, pushing your abdominal muscles and stomach away from your spine.

Your diaphragm needs space so it can move, and moving your abdominal muscles perpendicular to your spine gives the diaphragm the room it needs to work.

To think about the benefits of deeper abdominal breathing through the diaphragm another way, consider how you breathe through your chest for a moment (the unconscious way humans breathe). This type of breathing is often called shallow, or thoracic, breathing. Consciously, give it a try by simply trying to expand your lungs.

Notice how your lungs don’t seem to fill and empty fully for two reasons: 1) your ribcage does not allow the intercostal muscles in the chest to move much, meaning they do not force the lungs to significantly inflate or deflate, and 2) without your abdominal muscles and stomach moving, the diaphragm has less space to move and, consequently, your lungs are filled and emptied less.

Breathing While Playing

How’s this all relate to disc golf? Besides the physiological benefits brought by diaphragmatic breathing, this practice also benefits one’s mental state. Stepping up to a big putt or staring down a narrow tee shot can be nerve wracking. In a practical sense, deeper breathing can lower one’s heart rate and blood pressure and relieve mental fatigue, especially in tense situations. Additionally, continued shallow breathing through the chest during times of acute mental stress can further exacerbate tension in the upper body.

Relatedly, it is important to focus on when you’re breathing in relation to when you are throwing or putting. Typically, it is best to begin performing a movement just after exhaling, when your muscles are most relaxed and unencumbered.

For example, if you’re sitting at home right now reading this, try breathing in and holding it in for 15 or 20 seconds. Notice how your muscles, particularly those of your upper body, feel. You should feel tightness through your chest, shoulders, and neck. Muscles distracted with the responsibility of holding air in your lungs are not going to easily be put to use while you’re attempt a throw or a putt.

Next time you’re practicing putting, try to consciously breathe in and out fully a few times using your diaphragm, and then putt after having exhaled. Try this again, only attempt to putt after having just inhaled. Consider how each putt felt, not whether the disc went in or not. Was one more ridgid, while the other felt smooth?

Practice Makes Perfect

Breathing is naturally an unconscious activity; it happens whether we tell ourselves to do it or not. How we breathe, though, can be a conscious activity, and consciously making diaphragmatic breathing an unconscious part of our daily, athletic lives takes just as much practice as tweaking your backhand form or working through hitches in your putting mechanics.

I learned about this breathing technique while running cross country in college. It took about three or four weeks of focusing on how I was breathing — making sure to breathe through my abdomen — while out on my daily runs to get to the point where abdominal breathing became my default, something unconscious that I did not need to remind myself to do.

If this is something you think could benefit you, next time you’re out for a practice round pay attention to how you’re breathing. Take 10 or 15 seconds before you approach your lie to think about breathing though your abdomen, notice what it feels like and how to do it repetitively. As you walk down the fairway to your lie, or while you wait for a cardmate to throw, focus on inhaling and exhaling through your diaphragm rather than obsessing over the relative difficulty of your next throw or putt.

Deeper abdominal breathing can certainly benefit both physical and mental aspects of our disc golf game, but like any other kind of athletic activity, it takes some practice for it to become second nature. Luckily, this is something that can be easily practiced anywhere: on the course, at work, or while you commute. If you’ve got any questions, drop them in the comments section below and I’ll do my best to answer them.