One writer's deep dive into the voluminous resources for help inside the circle

December 20, 2016 by Josh Woods in Instruction with 0 comments

Editor’s note: This is the first in a three-part series about the resources available for putting instruction on YouTube and will discuss the demographics and skill level of instructors. The second piece will focus on the specific techniques advocated by instructors, while the final installment will highlight the putting styles of the top 50 players on tour.

Disc golf has developed, and quite successfully, without much help from large-scale institutions. In other words, most of us learn how to putt, use a mini, throw a sidearm, and play in tournaments without assistance from mom and dad, without a school system, without a church, without ESPN or Nike, and without a widely-accepted set of social norms that direct the masses to play.

To a social scientist, this aspect of disc golf is, in a word, weird.

Few other sports have existed as long and grown as large without support from massive private investment and a mainstream cultural footing. Few other sports have taught their followers, built their venues, invented their equipment, spread their rules, and shaped their values through such a diffuse network of individuals and groups. While many athletes are drawn to the ready-made, institutional sports of football, baseball, and basketball, the average disc golfer must find the still-developing, post-embryonic stage of disc golf attractive, if not liberating. Otherwise, the sport wouldn’t exist.

Compared to mainstream sports, disc golf is still in an early phase of institutional development. The question is, what happens to a sport when so many people play a role in developing it? How does it reach consensus on the basic principles of the game? Or are conflict and disagreement the perennial conditions of disc golf?

With that in mind, I recently began studying one of the sport’s greatest questions: How should novice disc golfers be instructed to putt? If a new player asked a room full of veteran disc golfers this question, half the room would likely recommend one of five different techniques (or all of them), and the other half would protest the question itself, suggesting that there is no one best way to putt.

I’ll discuss this controversy further in a future article. For now, I’d like to summarize the study and introduce its subjects.

Building a comprehensive playlist

In late November 2016, I searched YouTube using the term disc golf putting clinic, and carefully examined each link in the results. After excluding unrelated videos, the total sample included 58 different instructors. (For more about the selection procedure, see the appendix below.) Videos that included more than one instructor were broken into separate units of analysis, which produced a total sample of 82 appearances.

For each appearance, I noted the name of the instructor, the date it was posted on YouTube, the total number of views, the average views per day, and the URL. I also collected data from the PDGA directory on each instructor, including his or her city, state, PDGA number, and current rating. The directory contained complete information on only 46 of the 58 instructors.

Who are the teachers, where are they from, and how well do they throw?

Disc golf instructors on YouTube are similar in three respects. First, they are predominantly male; women comprised only 4.9 percent of the total appearances (4 out of 82). The percentage of women in YouTube putting videos is smaller than the percentage of female PDGA members, which stood at 7.4 percent in 2015, according to the PDGA.

Second, while I did not formally categorize the instructors by their racial characteristics, the percentages of black and Latino disc golf instructors were obviously lower than their shares in the general U.S. population. These findings support a previous study by Oldakowski and McEwen, who found, based on a small random sample, that 85 percent of disc golfers were male, and 95 percent were white1.

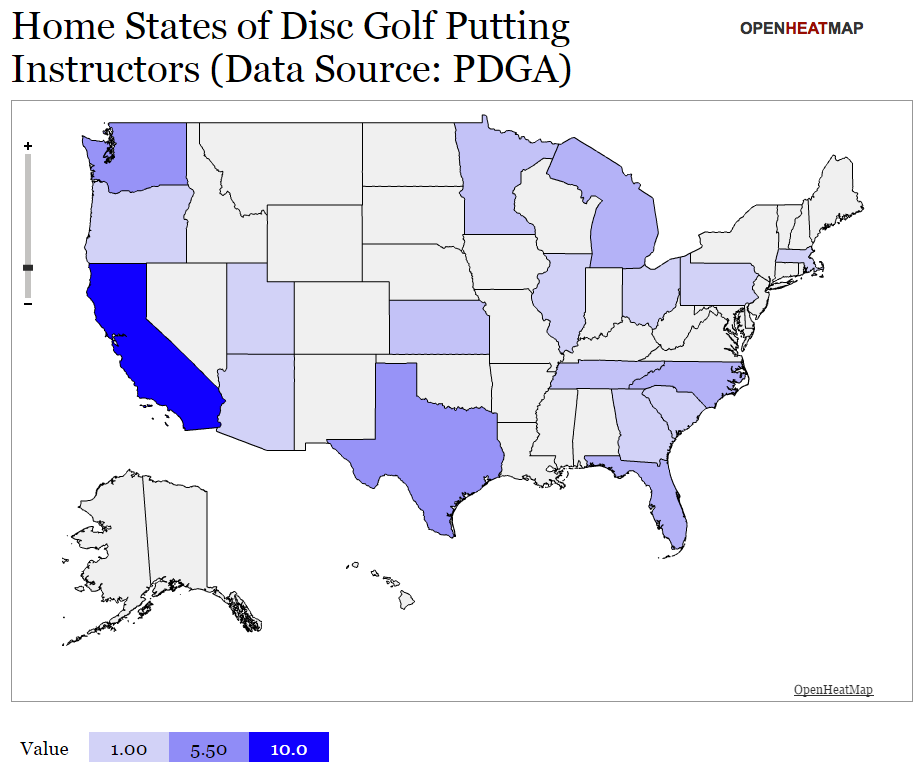

Third, the population is highly concentrated in certain regions of the country. As illustrated in the map below, 29 of the 46 instructors (63 percent) are from one of six states (California, Texas, Washington, Michigan, North Carolina, Florida). Only eighteen U.S. states and two foreign countries (Finland and Sweden) are represented in the sample.

Although most instructors appeared in only one video, Dave Feldberg and Ricky Wysocki appeared in five and four videos, respectively. Philo Brathwaite, Avery Jenkins, Nikko Locastro, Eric McCabe, Steve Rico, and Scott Stokely each made three appearances. Five other instructors appeared in two videos.

Most of the videos had been available on YouTube for more than three years. The average video was viewed 33,191 times — roughly 29 times per day. The video with the greatest number of views (308,622) was posted on June 4, 2009, and featured Scott Papa, who serves as Discgolfer Magazine’s instructional editor. The second most popular video, released April 16, 2012 by Discmania (280,646 views), showcased the teaching of Avery Jenkins and Jussi Meresmaa.

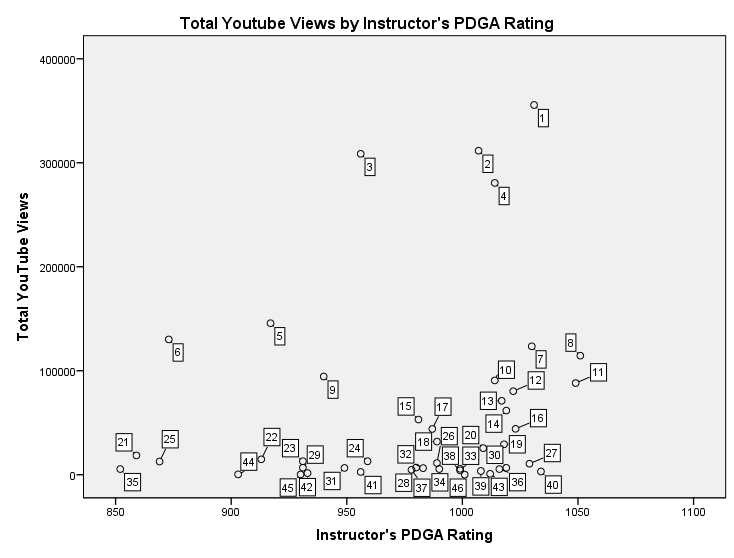

The instructors’ PDGA ratings ranged from 852 to 1051. The teachers who appeared most frequently and whose videos received the greatest number of views tended to have higher PDGA ratings than instructors who appeared less frequently and received fewer views. There was a small positive correlation between the instructors’ PDGA ratings and the view counts (r = .187, n = 46). This relationship was not statistically significant (p = .213).

As illustrated in the figure above, there were many instructors with high PDGA ratings who received a low number of YouTube views, and some instructors with low PDGA ratings who received a high number of views.

The takeaways

What are the “takeaways” from this study? First, women and racial minorities are underrepresented in the arena of disc golf putting instruction on YouTube. While white men make up only 31 percent of the U.S. population, they account for almost all the video appearances.

Decades of social research has concluded that people often learn new things and develop new behaviors by observing other people2. Key to this research tradition is the finding that people are more likely to learn from models who are like them. In other words, the role models who are most likely to inspire us, motivate us, and teach us are the ones with whom we identify, the ones whose life experiences seem to match our own, the ones who look and sound like us3.

Any strategy to “grow the sport” should take these simple ideas to heart, and focus on overcoming the under-representation of women and minority groups in disc golf. A small move in this direction might be as simple as creating more disc golf instructional videos that feature women, blacks, Latinos and other minority groups. Given the importance of role models, a series of small-scale, social media-based efforts could make a meaningful difference.

This study also illustrates the sport’s geographical disparities. Disc golf putting instructors reside predominately in regional hot spots, such as California, Michigan, and North Carolina. The findings suggest that some disc golf communities located outside these hot spots may have lesser access to face-to-face disc golf instruction with high-rated pros.

Despite the gender, racial, and geographical homogeneity of the disc golfer population, the instructors differed greatly in terms of their age, skill level, teaching styles, recommendations, and popularity. The sample included two junior disc golfers and at least one instructor who is closing in on his 70th birthday. Disc golfers from all divisions and skill levels were represented in the sample.

Top 20 Most Viewed Disc Golf Putting Instructors on YouTube (Watch Now)| Name | PDGA Number | State | PDGA Rating | Number of Appearances | Total Views |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dave Feldberg | 12626 | AZ | 1031 | 5 | 355,561 |

| Avery Jenkins | 7495 | OH | 1007 | 3 | 311,627 |

| Scott Papa | 10099 | WA | 956 | 1 | 308,622 |

| Jussi Meresmaa | 14600 | Finland | 1014 | 1 | 280,646 |

| Dave Dunipace | 987 | CA | 917 | 2 | 145,738 |

| Steve Carson | 18949 | WA | 873 | 1 | 130,152 |

| Nikko Locastro | 11534 | CA | 1030 | 3 | 123,484 |

| Paul McBeth | 27523 | CA | 1051 | 1 | 114,522 |

| Mark Ellis | 7423 | MI | 940 | 1 | 94,476 |

| Will Schusterick | 29064 | TN | 1014 | 1 | 90,733 |

| Ricky Wysocki | 38008 | SC | 1049 | 4 | 88,203 |

| Ken Climo | 4297 | FL | 1022 | 2 | 80,368 |

| Eric McCabe | 11674 | KS | 1017 | 3 | 71,131 |

| Cameron Todd | 12827 | NC | 1019 | 1 | 61,765 |

| Gregg Hosfeld | 1602 | FL | 981 | 1 | 53,119 |

| Steve Rico | 4666 | CA | 1023 | 3 | 44,170 |

| Justin Drage | 21545 | GA | 987 | 1 | 44,091 |

| Dan Beto | 31408 | MN | N/A | 1 | 41,172 |

| Scott Stokely | 3140 | NC | 989 | 3 | 31,916 |

| Philo Brathwaite | 26416 | CA | 1018 | 3 | 29,297 |

As shown in the table above, many of the instructors with high YouTube view counts are well-known, highly-rated professional disc golfers. Overall, however, PDGA rating was a surprisingly weak predictor of the number of views. For example, the putting instructions of two-time world champion Barry Schultz (#40 in the scatter plot), and five-time world putting champion Jay Reading (#38 in the scatter plot) received relatively few views on YouTube. View counts were also lower than expected for Josh Anthon, JohnE McCray, Gregg Barsby, Tim Skellenger, and others.

As I’ll show in a future article, the instructors rarely discussed principles from sports science when giving advice on putting technique. In fact, most of the instructors offered no explicit advice on which putting technique to adopt, and some claimed that such a recommendation could not be made. Among those instructors who did prescribe a specific putting technique, there was a great deal of disagreement about the most reliable or “best” way to putt.

Learning how to putt is a beautiful and terrible love affair. In one moment, our putt can fill us with joy and confidence, and in the next, it can ground us in the dirt. In the tough times, when our confidence is shot and nothing makes sense, we look to the pros. For many of us, this means watching instructional videos online. What we find—a bewildering mass of conflicting views and a sea of agnosticism—is not always comforting. In disc golf’s post-embryonic stage of institutional development, a definitive guide to putting does not yet exist.

Appendix

Resources

To watch the twenty most viewed disc golf putting videos on YouTube, see my channel. I’ll be adding playlists to highlight other aspects of putting advice on YouTube soon.

YouTube video selection procedure

To collect a sample of videos, I searched YouTube in late November 2016 using the phrase disc golf putting clinic. My search returned 560 video links. I sifted through each of these links to determine whether it should be included in a sample of disc golf putting clinics. I carefully excluded duplicate clips. I also omitted clinics on putting from a distance that exceeded roughly 10 meters. This study pertains to putting clinics “inside the circle” and cannot be applied to jump putts and other long distance putting techniques. Finally, I excluded instruction on rarely used specialty putts, putting under unique environmental conditions, footage of putting competitions, putter review videos, putting compilation videos that lacked verbal instruction, demonstrations of putting games, instruction given in foreign languages, and parodies of disc golf putting instruction.

After excluding unrelated videos, the sample of videos included 58 different instructors. Videos that included more than one instructor were broken into separate units of analysis. Some instructors also appeared in more than one video. For this reason, there were a total of 82 units in the sample.

This sample is not representative of the entire population of publicly available videos on putting. The goal was to collect a large sample of videos that likely emerge when disc golfers search YouTube or Google for putting instruction and clinics. Other search terms and search engines may return different results. This is a preliminary study based on merely suggestive evidence.

Oldakowski, R., and J. W. Mcewen (2013). Diffusion of disc golf courses in the United States. Geographical Review 103(3): 355-371. ↩

Bandura, Albert (1963). Social learning and personality development. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ↩

Bandura, Albert (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ↩