Social research suggests two strategies for growing the sport

March 10, 2017 by Josh Woods in Analysis with 1 comments

Drew Barrymore directed and starred in one of my favorite movies. Whip It, released in 2009, tells the story of a misfit teen from Texas who finds refuge from the doldrums of small-town life by joining a women’s roller derby team called the Hurl Scouts.

In one scene, the Hurl Scouts come together after a bout. Despite losing the hard-fought contest, the women are all smiles and fist pumps and laughter.

Razor, the male coach of the Hurl Scouts, is beside himself in disbelief as his team joyously chants, “We’re number two! We’re number two!”

“You guys came in second out of two teams,” Razor retorts.

The team chants even louder.

“Yeah, let’s celebrate mediocrity,” says Razor, sarcastically. “That’s fantastic.”

Since the film’s debut in 2009, I’ve shown this scene to no fewer than 500 college students in my course on social psychology. Some students find the Hurl Scouts’ display of happiness in the face of defeat ridiculous and implausible. Others describe the team’s free-spirited reaction as a refreshing alternative to the play-to-win mindset of traditional sports.

The class debate typically divides along gender lines and gravitates toward the question of what motivates people to play sports. Do women and men compete for the same reasons?

Social scientists have been answering this question for decades, and their findings may be informative to anyone interested in growing the sport of disc golf.

Studies of motivation outside the realm of sports have shown that competitiveness is more likely to motivate men than women1. Within the sports domain, several researchers have reported that male athletes, on average, are more motivated by the prospect of beating the competition than female athletes2.

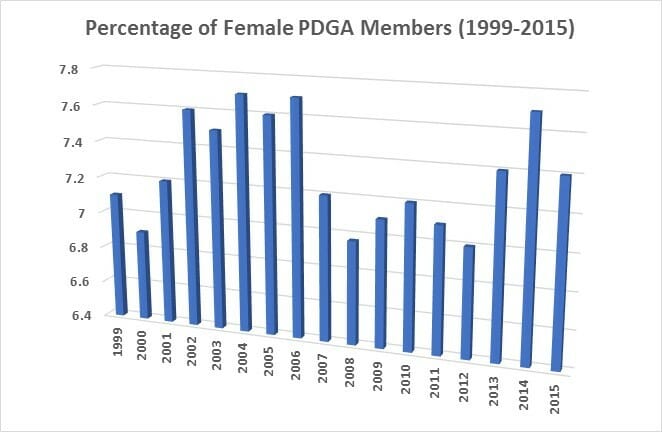

There are no studies on the motivations of disc golfers, but the topic has emerged in the ongoing discussion of disc golf’s notably low participation rate among women. Per the Professional Disc Golf Association, between 1999 and 2015 the share of women among PDGA members has stayed within a range of 6.9 percent to 7.7 percent.

Asked about how a competitive atmosphere might influence women’s participation in local league events, four-time PDGA World Champion Valarie Jenkins said it might not have much appeal.

“Results-based competitions – based on tags or score – that’s what really drives the men,” Jenkins said. “That’s a guy’s mentality. The women’s mentality is more about the social aspect…You can’t run a women’s league in the same style as a traditional mixed or co-ed league.” Similar statements about women’s-only events have been made by other female competitors and prominent disc golf organizers.

Meanwhile, as the overall share of female PDGA members stagnates, the popularity of women’s-only disc golf is on the rise. As one example, the first PDGA Women’s Global Event held in 2012 attracted 575 women; by 2016, the event included 63 tournaments and 1,629 participants. Interest in women’s-only events appears to be gaining ground at the grassroots level, as well.

There is no simple explanation for the success of these events, but there’s no doubting the enthusiasm of the women who play in them. When asked about how women’s-only events change the way participants experience disc golf, Jenny San Filippo, the president of the Disc On! Ladies League in Wisconsin, described an infectious setting.

“I think the excitement level goes up 100 percent,” San Filippo said. “There’s always this crazy, weird, positive energy. And everyone is supportive of each other.”

Jenkins agreed.

“The main thing is the atmosphere,” Jenkins said. “There’s so much energy that revolves around a women’s tournament.”

Hearing about women’s-only events reminds me of the Hurl Scouts in Whip it, and the team’s paradoxical jubilance in the face of defeat. After my most recent screening of this scene in class, a female student justified the Hurl Scouts’ reaction by saying, “There’s more to winning than winning…Most guys just don’t get it.”

The “it” to which she referred goes by many names: solidarity, social integration, collective soul, group cohesiveness, cooperative interdependence, relational togetherness, “crazy, weird, positive energy.” Though terminological disputes exist, the positive effects of this kind of social cohesion on group outcomes are undeniable. Dozens of studies have shown that members of highly cohesive groups communicate more effectively, have greater influence on each other, and feel more emotionally satisfied than members of less cohesive groups3. In short, it may be one of the keys to growing disc golf, and women’s-only events seem to have a lot of it.

The differences in motivation between male and female athletes hold important implications for disc golf, but there is at least one conclusion that should not be drawn. The idea that women are less competitive than men by nature is not supported by scientific research, nor by anecdotal remarks from female disc golfers.

In fact, at the highest levels of professional athletics, the mentality of male and female competitors is probably quite similar. For example, when asked in a recent email discussion about what motivates professional disc golfers, Jenkins wrote, “For professionals to compete at the highest level, they must be competitors, physically and mentally. In the end, it’s only you out there throwing the disc…and you don’t always have a support system behind you. You have to use your experience and feed off of your motivating mental game to carry you through. I do think that is the same for men and women.”

Given the obvious challenges of surveying celebrity athletes, I found only one study of elite professionals. Researchers surveyed 155 professional tennis players and found, based on a robust measure, that “female tennis professionals scored higher on sport competitiveness than males4.”

The takeaway here is straightforward: The mentality of athletes depends not on their sex, but on the social context in which they play. If the movers and shakers of disc golf believe that a more competitive mindset among women will stimulate growth in the sport, they should consider making the context of women’s disc golf more competitive.

A first step in this direction would be to include an Open Women’s division at all the major professional events. After receiving criticism for its “one division” policy in 2016, the Disc Golf World Tour (DGWT) added a women’s division at three of its four events in 2017. Still, the DGWT’s final stop, the United States Disc Golf Championship, remains a “one division, one champion” event, which limits the number of women who will play – Paige Pierce has qualified, and the winner of the United States Women’s Disc Golf Championship is granted a berth — and certainly lessens the chance a woman would be the Disc Golf World Tour Champion.

A second step would be to increase payouts for women. According to a study by World Champion Sarah Hokom, “women are making around 40 percent of what the men make at the most elite level.” At the 2017 Aussie Open, for instance, the first place male finisher received $4,000, while the first-place female took home $1,100. This is necessarily a byproduct of smaller women’s fields, but distributions of added cash can be augmented.

Differences in prize money not only deflate the competitive mentality of female disc golfers, but they makes participation at some events financially unviable. Why would a large group of American women play a tournament in Australia, knowing that the top prizes won’t even cover the cost of travel? The pay gap may also discourage some institutional sponsors from supporting competitive disc golf, given the equal opportunity requirements of Title IX, not to mention the public’s growing distaste for gender inequality in sports.

Still, inroads have been made toward this end. While most events see women garner a lower payout due to the smaller number of participants, sponsors have started to change their habits. Discraft announced this week that women are on the same bonus structure as men, and Catrina Allen has confirmed in the past that the same holds for her sponsor, Prodigy Disc.

Finally, given that media coverage heavily favors men’s events, increasing the coverage of women would also reinforce the competitive mindset of female disc golfers.

Other sports, such as professional tennis, have already made strides toward event inclusion, as well as wage and media equality. Thanks to determined advocates like Billie Jean King and Venus Williams, pro tennis is one of the few sports where men and women compete together in the same stadiums and receive equal pay at major tournaments.

The case of pro tennis, coupled with scientific research on the motivation of athletes, suggests two strategies for attracting more women disc golf. The two formulas are, in some ways, contradictory, but both are required for either to succeed.

Following the pro tennis formula, disc golf needs tournaments where men and women are equally motivated to play and win, thus impacting the professional pool of players. Following the Barrymore formula, disc golf also needs events that depart from the typical, competitive, male-dominated league or tournament — events where women compete in a more social, encouraging atmosphere, and some even celebrate when they come in second place. Combined, these two routes can, over time, result in increased participation from women and greater gender equity in the sport.

Croson, R., and Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47, 448 – 474; Wilson, M., and Daly, M. (1985). Competitiveness, risk-taking, and violence: The young male syndrome. Ethology & Sociobiology, 6, 59–73. ↩

Gill, D. L. (1988). Gender differences in competitive orientation and sport participation. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 19, 145–159; White, S. A., and Duda, J. L. (1994). The relationship of gender, level of sport involvement, and participation motivation to task and ego orientation. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 25, 4–18; Nien, C.-L., and Duda, J. L. (2008). Antecedents and consequences of approach and avoidance achievement goals: A test of gender invariance. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9, 352–372. ↩

DeLamater, John D., and Daniel J. Myers (2010). Social Psychology, Boston, MA: Cengage. ↩

Houston, John M., David Carter, ad Robert D. Smither (1997). Competitiveness in elite professional athletes. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 84 (3c): 1447-1454. ↩